The Forge and the Canvas: Blacksmithing in Art

- Aidan Mackinnon

- Aug 18, 2025

- 4 min read

While many today associate blacksmithing with the fierce flames and dramatic challenges of shows like Forged in Fire or the viral videos of YouTube creators, the art of the forge has been a subject for artists for centuries. Long before the camera captured the precise moment of a hammer's strike, painters found beauty and meaning in the blacksmith's labor, elevating a practical trade to the realm of high art.

Joseph Wright of Derby and the Industrial Sublime

One of the most compelling painters of the industrial age was Joseph Wright of Derby. A master of light and shadow, he was fascinated by the glowing furnaces and dramatic scenes of the burgeoning Industrial Revolution. He completed several paintings of blacksmiths, with his most famous being 'An Iron Forge' (1772). In this piece, Wright masterfully uses chiaroscuro to highlight the muscular forms of the workers and the intense glow of the forge, transforming a scene of manual labor into a powerful and almost sacred spectacle. The painting captures not just the physical work, but the profound human connection to fire, creation, and industry.

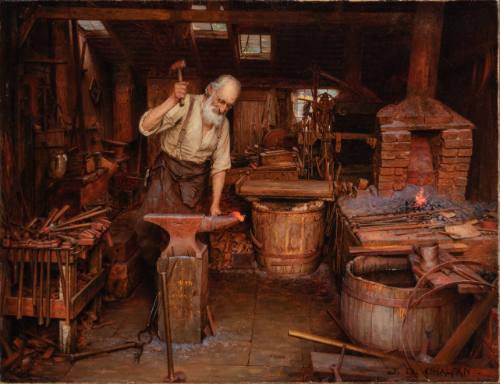

The American Forge: Chalfant and Nagle

Across the Atlantic, American artists also turned their attention to the blacksmith. Jefferson David Chalfant's work, 'The Blacksmith' (1888), is a detailed and realistic portrayal of a craftsman at his work. The painting is a testament to the artist's attention to detail, from the tools scattered on the floor to the concentration on the blacksmith's face.

Similarly, John Nagle's 'Patrick Lyon in the Forge' (ca. 1826) is a remarkable portrait that places its subject, a master locksmith, in his natural element. The painting celebrates the dignity of labor and the skill of the individual artisan, capturing a moment of quiet, focused work. The piece was commissioned by Patrick Lyon with the note;

"I wish you, sir, to paint me at full length, the size of life, representing me at the smithery, with a bellows-blower, hammers and all the et-ceteras of the shop around me. I wish you to understand clearly, Mr. Neagle, that I do not desire to be represented in this picture as a gentleman—to which character I have no pretensions. I want you to paint me at work at my anvil, with my sleeves rolled up and a leather apron on. I have had my eyes upon you. I have seen your pictures, and you are the very man for the work."

Classical and Spanish Visions: Velázquez and Goya

The motif of the blacksmith was also a powerful vehicle for storytelling in European art, particularly in Spain. Diego Velázquez's 'Vulcan’s Forge' (1630) is a brilliant example, depicting the mythological god of the forge, Vulcan, in his workshop. The painting is celebrated for its naturalism, showing the gods as muscular, everyday men in a realistic setting. Velázquez uses light to dramatic effect, drawing the viewer's eye to the radiant figure of Apollo as he reveals Venus's infidelity.

A generation later, Francisco Goya's 'In the Forge' (ca. 1817) offers a more grounded, powerful perspective. Goya’s work is less mythological and more a celebration of the sheer force and physicality of the blacksmiths. The three men are shown in a tightly packed space, their bodies tensed in a shared effort to strike the hot metal. Goya’s powerful brushstrokes and use of shadow convey the raw energy and exertion of the work.

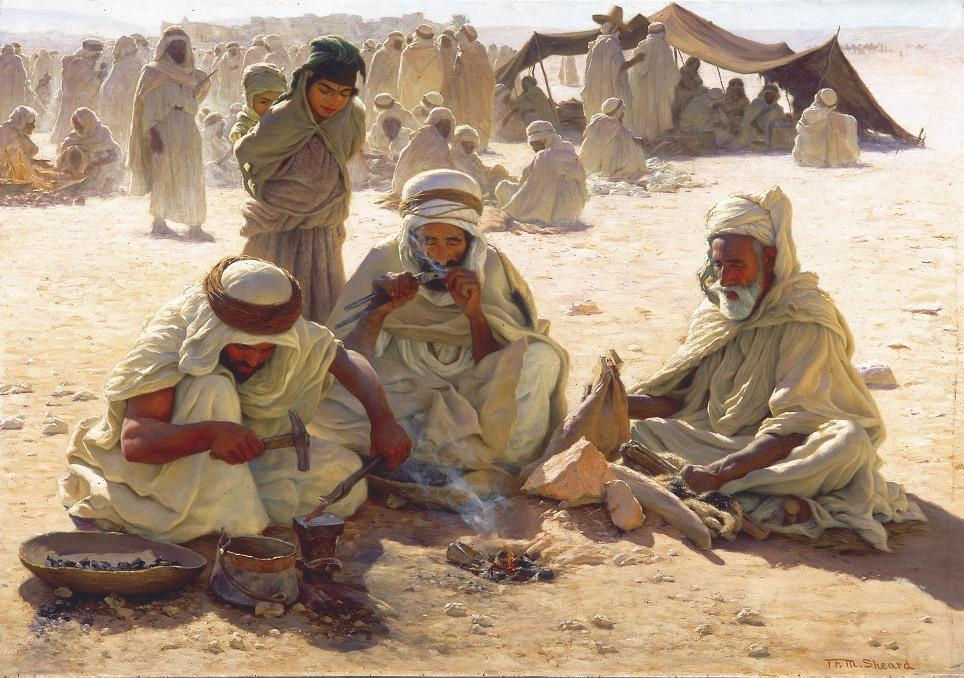

Orientalism and the Arab Blacksmith

The British academic painter Thomas Sheard (1866–1921) continued this tradition of depicting labor with his painting, The Arab Blacksmith (c.1900). This work, now in the collection of the Bendigo Art Gallery, is a captivating example of Orientalism—a 19th-century movement where European artists were fascinated with and often romanticized the cultures of North Africa and the Middle East. While Sheard’s painting is grounded in his travels to Algeria, its primary power lies in the masterful depiction of light. The dazzling sunlight of the desert and the dramatic glow from the forge are rendered with an almost Impressionist sensibility, revealing the artist’s preoccupation with conveying pure light. Sheard's work, completed in his studio and on a grand scale, transforms a scene of a semi-nomadic trader at his forge into an exotic and visually stunning tableau, showcasing how the theme of the blacksmith was adapted to fit new artistic and cultural movements.

Myth, Labor, and Master Craftsmanship: The Renaissance Rondel

The depiction of blacksmithing was not limited to the industrial age. Perhaps one of the most exquisite fusions of blacksmithing, art, and mythology is a bronze rondel acquired by the Metropolitan Museum of Art. At 16.5 inches in diameter with gilded accents and silver inlay, it is the largest known bronze roundel from the Renaissance. The piece beautifully depicts a scene from Roman mythology: Venus and her lover Mars flirting while her husband Vulcan labors at the forge.

The scene is rich with symbolic detail: Venus sits in the center with Cupid on her lap, his arrow aimed at her breast, while her wings are partly visible. Mars is armed, and Vulcan is captured mid-strike, working on a helmet embossed with a horse. The Latin inscription below the scene, “CYPRIA MARS ET AMOR GAVDENT VVLCANE LABORAS,” translates to “Venus, Mars and Cupid enjoy themselves while Vulcan works.” This popular motif in northern Italy in the late 15th and early 16th centuries highlights the contrast between the leisurely pursuits of love and war and the relentless toil of the craftsman.

Elevation of the Daily Toil

While many of these historical paintings of blacksmiths are often seen as illustrations of the Industrial Revolution, the depicted technology itself isn't what makes them modern. Instead, their true innovation lies in their heroic and dignified treatment of everyday life. At the time, art theory held that such a common scene of working men didn't deserve a grand style. Yet, through extraordinary light effects and dramatic composition, these artists imbued the forge with an almost religious grandeur. The subtle allusions to themes like the 'Ages of Man' elevate these prosaic subjects, making them worthy of the masterpieces they are.

Comments